3D digitizing technologies have been utilized in the industrial world for the last 20 years but are increasingly used in many other fields. One of the exciting, but unanticipated, uses of 3D measurement tools has been their adoption by museums for sculpture conservation, research, and interactive exhibits.

3D scanning is a perfect fit for documenting museum pieces. Museums, for example, typically have pieces that cannot or should not be touched, yet present tremendous opportunity for study, documentation, interactive presentation, or scaled or one-to-one reproduction. The great news is that with one scan, all of the above can be achieved without any physical contact with the work of art.

Direct Dimensions first became involved with scanning sculptures for research purposes in 2004 when they were approached by the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) to scan two castings of Antoine Louis Barye’s Tigre qui Marche (The Walking Tiger). The BMA was interested in dimensionally inspecting and comparing two of the (many) existing castings. Direct Dimensions laser scanned the two tigers with a Faro Scan Arm and overlaid the two resulting 3D models to compare them.

The BMA was so pleased by the outcome of the Barye effort that they engaged Direct Dimensions again, on a much larger project. In 2007 and 2008 they mounted a large show, Matisse: Painter as Sculptor and the curators were interested in applying some of the same 3D scanning techniques to their research. In particular, they were interested in how the technology might illuminate the creative process of Matisse as a sculptor.

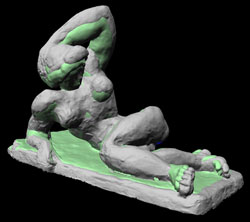

The Direct Dimensions team focused on two sets of sculptures: different castings of Matisse’s Reclining Nude I (Aurora) and Madeleine I & Madeleine II. In the case of the Reclining Nude, curators were interested in comparing multiple castings to see how they may be related to one another. As for the Madeleines, there was a theory that Madeleine II had been cast from the plaster cast of Madeleine I. BMA curator Ann Boulton hoped that a dimensionally accurate inspection (detecting differences as small as tenths of a millimeter) might shed light on the theory.

After working closely with the BMA staff to understand their research interests, the 3D scanning technicians opted to use a Faro Arm and Faro Laser Line Scanner. The arm and scanner combination can capture the data with an accuracy of +/-0.002”, allowing every fine, hand-worked detail to be captured without ever touching the sculptures. The arm and scanner are also portable so the artwork never left the safety of the museum.

Back in their office over the next few weeks, the DDI team used Innovmetric’s PolyWorks Modeler software to process the raw laser data into 3D digital replicas of each of the sculptures. The 3D models of both set of sculptures, the Reclining Nude I (Aurora) and Madeleine I & Madeleine II, enabled exciting discoveries.

The three models of Reclining Nude I (Aurora) were superimposed over one another in a dimensional analysis. The superimposed image is visualized as a color mapped figure that shows where the castings deviate from each other. The team at Direct Dimensions and the BMA discovered that two of the casting were essentially identical (both had been cast from the same mold) while the third was approximately 4% smaller, indicating that it was a “cast off” or copy of one of the originals.

The Madeleine I & Madeleine II analysis differed from the Reclining Nude I (Aurora) because entire superimposed models were not necessary. The curators were trying to find specific similarities, so the team at Direct Dimensions took specific cross sections from each of the models and compared the cross sections. The results from the cross section analysis indicated that though large parts of the sculptures were different, the close measurements in the torso and head section indicated that the second sculpture was indeed created from the first. This major discovery was an important insight into Matisse’s artistic process.

In addition to enabling important research, the 3D scan data was used in two multimedia presentations supporting the exhibit. The same data used for the research and presentations can also be used to create high quality replications.

The Matisse: Painter as Sculptor exhibit is just one example of a fine art application for 3D scanning and imaging technologies. Recently, Direct Dimensions has also worked with MOMA, The National Gallery of Art, The Getty, The Walters Art Museum and of course, The Baltimore Museum of Art on additional conservation and research projects. 3D scanning for technical examinations of museum collections is just starting to gather steam and it is exciting to imagine what future research will bring.